I came to Cascadia in 1977,

though I didn’t call it that then. The

Cascadia idea was still emerging. Bates

McKee’s 1972 tome on regional geology, Cascadia:

The Geologic Evolution of the Pacific Northwest, was the source of the idea

for many. A unique land nested on the

Pacific Rim, place of volcanoes and mountain chains, great rivers and deep,

verdant forests.

Great places need great

storytellers and visionaries to help us know and see them. My journey through this place has been informed

by a great Cascadian visionary, David McCloskey. David elucidated many of the original

thoughts about Cascadia as a bioregion, what defines it as a unique place. He

helped me shape my own thoughts about this place and my commitment to it. A great mapmaker, David travelled the

bioregion and felt out its boundaries. I

resonate with them.

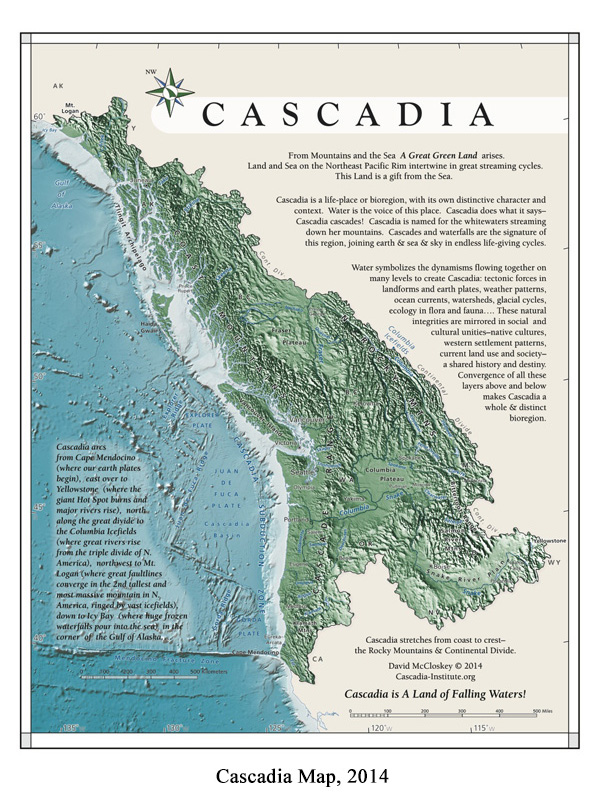

Now David is making new and

more detailed maps of Cascadia. Here is

the latest from his Cascadia Institute

site.

“This new map shows a real place, not an abstract nor ideal

space," David describes. “The life of our

bioregion has been obscured, split up by boundaries and separated into

categories, the matrix dismembered. This map reveals something important that

has long remained invisible—namely, the integrality of the bioregion we are

calling 'Cascadia.' This map provides a portrait of home....”

“Every place, as with every person, has

its own story to tell,” David writes. “For ‘A place is a story that happens many

times,’ as the Oregon writer Kim Stafford reminds us.

“The power and beauty and tragedy of

this place is palpable, its promise still to be fulfilled. This place is

a story unfolding on many levels. The new story we seek to tell here is

not simply the ‘re-telling’ of history, for most of it awaits discovery.

“We are called to become explorers in

our own lands, to rediscover an originary map of the world, so that

we may find our way home.”

My Cascadian exploration has

been just that, exploring across the landscape, finding my own way home.

I grew up in the Northeast

power corridor, the megalopolis that stretches from Boston to Washington, in

the middle of it on the outskirts of Philadelphia. It was a very East Coast existence. I recall the 3 a.m. smell of a public men’s

room in Manhattan on late teen excursions over to The City taking advantage of

New York’s then loose-as-a-goose 18-year-old drinking age. (I wasn’t.) I can still bring up vivid pictures of the

headlight-illuminated snake of traffic streaming down the Pennsylvania Turnpike west

of Philly, Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit in the Sky” rocking in time on the

radio. Somehow it seemed the essential

expression of postwar American life.

I remember mom and dad taking

us to the New York ’64 World’s Fair and the top of the Empire State Building,

still the world’s tallest. And living in

DC going to Georgetown taking Bill Clinton’s favorite historian, Carroll Quigley. I might have been a lifetime

East Coaster. But some muse drew me

invariably West. I wound up in LA where

I took journalism at Cal State-Long Beach.

After graduation I was standing on a point overlooking the Pacific on a clear, starry night feeling a stiff wind blow in my face. Seemed like a north wind. I felt called to the Northwest, not knowing

much about it.

I came with an imagery of the Pacific Northwest, a kind of “Five Easy Pieces” vision of a green land far away from most everything. Somewhere in my mind were stuck educational comic book drawings of loggers and salmon, snow-capped peaks and big trees.

Those were the days when I

could still pack my belongings in my car.

In late 1977 I drove up I-5 and pulled into Seattle a few years after

the post-Vietnam recession and that famous billboard, “Will the last person

leaving Seattle please turn out the lights?”

The lights were beginning to come back on. But it was still funky old Seattle. Starbucks was a small, local coffee chain.

Microsoft was a start-up run by two guys named Bill and Paul chasing software dreams in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Kurt Cobain was an abused 10-year

old in Aberdeen-Hoquiam. The “boxes in which the Space Needle came” were just beginning to pop up in the downtown skyline.

Chasing a journalism job I

was quickly drawn over the mountains to the farm teams of county weeklies and

small dailies. So unlike many

transplants who move from some metropolis elsewhere to the Northwest urban equivalent, I actually experienced the country east of the mountains and am

richer for it. I got to cover everything

from the Omak Stampede rodeo to Indian reservation mining struggles.

But after three years I

tired of mainstream journalism and moved to Portland to focus my real life

pursuit, advocacy journalism and organizing.

It put me at the seedbed of things.

The early days of ancient forest activism. The early stirrings of ideas that cities actually

could be green and sustainable. The early version of this Cascadia Planet

website in the mid-1990s, one of the world’s first explicitly bioregional

sites. And early efforts to shape a

regional response to global warming, a pursuit I continue to this day back in Seattle.

It was a landscape from which

all of this grew, a place so deep and stunning in its natural beauty it could

grab my East Coast soul and transform it into something of its own. I once heard Native American leader Winona

LaDuke advise us immigrants to “go back to the place you are native or become

native to the place.” I chose the latter, engaging in struggles and organizing

projects to preserve its great nature and build a sustainable society on its

landscape. I continue to act on the idea

that by acting in place, locally and regionally, we can build the

new in the shell of the old and actually make a sustainable world.

Cascadia has long been my

inspiration, even before I knew it was called that. It is a place that tells you there is a

planet worth saving, a direct engagement with the Earth that moves the

soul and spirit. McCloskey’s seminal

mapmaking has helped me see this place, and value it. May it help you my fellow Cascadians see it

as well, and move you to save this place and the beautiful planet in which it is

embedded by seeding a truly sustainable society in the region. It is what we have at hand to make a truly sustainable

world.

Fantastic post Patrick! Inspires me to think more closely about who and what I am doing my work for. For a long time the Sea-First tower was the dominant, solitary building downtown and we called it "THE box that the Space Needle came in." :-)

ReplyDeletewould hope this could be shared via the yahoo bioregional list serve

ReplyDeleteGreat suggestion, Debra! You'll see it soon.

Delete